Connecting Grassroots to Government

In the coming days, the growing connections between the crowd and US government agencies will become a major meme in the news. The stories will focus on how grassroots communities–digital volunteers–are transforming the way that the government processes data for development and emergency operations. As a board member of one of these organizations, it gives me great pleasure to see years of work finally gaining recognition. Thousands of volunteers are changing the world of information management. We need to celebrate this accomplishment and trumpet it loud and clear. And to thank those volunteers who have given so much time and skill through each of the various communities involved in crisis mapping.

But there is a backstory here and more credit due. As one of the facilitators who has helped the government champions create the interface between the grassroots and the government, I need to give testimony to dozens of federal employees who stuck their necks out to make this moment possible.

The Deeper Backstory

In Silicon Valley, there is a deeply held belief that technology can change the world. To some extent, that is true: a new tool can introduce rapid and catalytic change in a society, as did the automobile or the Internet. But every technical solution embeds into its design a belief about the nature of a problem. The automobile’s design captures the notion of independent, on-demand travel. The Internet’s design began from the need for a communication network that is not vulnerable to destruction of a central hub.

In emergency management, the design of current government tools reflects a tried and true belief: that making sense out of a disaster is a specialized task best performed by highly trained responders working in hierarchical command structures. New tools around crisis mapping and crowd sourcing conflict with this belief. Crowdsourcing platforms connect thousands of volunteers into a collective intelligence, enabling lightly trained volunteers to work in a sort of massively parallel human supercomputer. That said, because contracts, technologies, regulations, and even laws have been built around the mobilizing a small number of specialists, building the policy space for the grassroots to process data on behalf of the government is a huge challenge for federal employees. I cannot overstate how difficult it can be to find ways through the morass of unclear regulations and licenses written years ago for circumstances that have since dramatically changed.

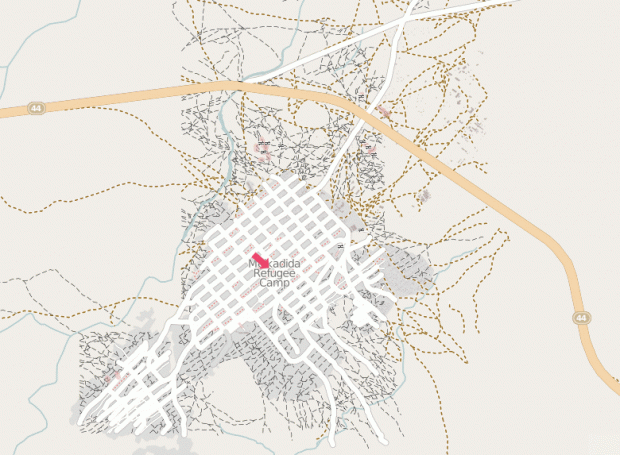

It has been my privilege to work with over four dozen government lawyers, technologists, and policy makers in a process to work through many of these issues. Over the past 18 months, this motley crew from multiple agencies has built (to our knowledge) the first official link between the grassroots and government for disaster response: an imagery workflow process that enables OpenStreetMap volunteers to trace high-resolution satellite imagery that is purchased by the US government from the private sector. (The results from last week’s test of the process can be found here). In parallel, others have worked around opening operational data, and that second workflow is culminating in the first release of economic data from USAID projects to the Standby Volunteer Task Force (see USAID announcement).

Both are successes. Both need credit. But we should realize that the people who made this moment possible are the champions in the US government who have been willing to conceive of open government and governance not in terms of apps created or portals launched, but in terms of policies that have been changed in ways that enable citizens to provide mutual aid, both within our nation as well as around the world. It is these people–many of whom will likely remain unsung and may wish to remain anonymous–who deserve a huge hurrah. Thank you from the crowd.