Humanitarian Songbook

As I awoke this morning to news that we might be replaying the Boxing Day tsunami from 2004 all over again, I watched the actions across my various email, skype, and twitter channels and got anxious. We have made so much progress on technology and practice since 2004, and we now have a community of dedicated and talented crisis mappers, and yet, our coordination is still not where it could be.

I realized that I had no ability to predict who was awake and who was working which issue. Did we need imagery; which areas of interest (AOIs) and when would the next potential satellite pass be? Did we need maps; how current are those areas in either Google MapMaker or OpenStreetMap? Did we have a method of pulling in social media and making sense of it; or would we wait for activation? Yes, had the emergency unfolded differently, we would have got to these questions eventually, but wouldn’t it be great if questions like these–or perhaps better ones–were deeply ingrained in all our heads, like a musician know his or her scales?

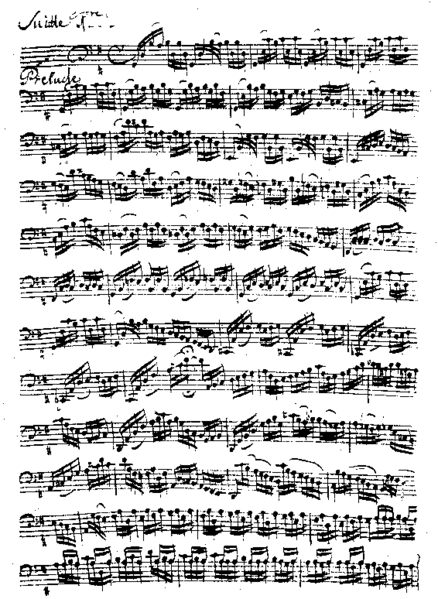

For a while now, I have been thinking about bringing concepts from jazz into humanitarian information management. As a classically trained cellist, I had to relearn to think in this way, as my experience has been very different. For thirty years, I was taught how to realize “scores”–musical blueprints that specify in great detail what each voice should be doing at any given moment in the music work. That approach works when you have a full understanding of the universe of possibilities–when the score is a completed architecture and just needs to be “recreated.” This is the approach of many disaster management agencies. That said, with disasters, improvisation is needed; we need to make the music as we go, and we cannot predict what any given actor will need to do at any one time.

That said, however ‘unspecified and unscoped’ the response operation may become does not necessarily mean we as crisis mappers need to be ‘out of harmony or rhythm.’ In jazz, there is a shared oral tradition that everyone learns: a set of melodies, harmonies, and rhythms and a morality around how to interact using those shared patterns in an ensemble. Together, musicians with such a common understanding can take even a fragment of a melody and create incredible structures that they did not have planned out when they played the first note. What if we had such a system for our crisis mapping work? What if we could know who is doing what with which tool and community, and how it all is weaving together into a (harmonious) whole, without over-specifying who does what or recreating ossified bureaucracies that move slowly?

Yes, we are making progress towards this end with shared protocols, trainings, and experiments. But we need to bring those efforts together again. We need to develop the ingrained, practical knowledge sometimes called metis.

I would like to advocate that we start work on such a song book, so that the next major disaster, we all have a basic song list to play off (with all the melodies, chords, and rhythms implied), and the ability to predict what each other will be doing, even if only in rough outlines. That way, we can improvise more effectively together.

Who wants to jam? We need to build some riffs.